Jessie Krause and Alex Kessler can’t sleep. Their bedroom is flooded each night by several bright lights from neighboring properties, beams shining straight through their window until morning. The effect, they say, makes their home feel “like a prison yard.” Yet despite repeated requests for the glare to be reduced, nothing has changed.

The problem keeping them awake is known as light trespass — artificial light shining where it isn’t wanted. As bright outdoor lighting becomes more common, light pollution, of which light trespass is a subcategory, has become a growing concern in communities everywhere.

Light pollution is more than an annoyance. A rapidly expanding body of research shows that nighttime exposure to artificial light disrupts circadian rhythms, which play a key role in human health. And brighter isn’t necessarily safer: harsh or unshielded lights can create glare that reduces visibility. Artificial light at night also harms ecosystems by disrupting the biological rhythms that guide migration, feeding, hunting and reproduction.

For Krause and Kessler, though, the steepest cost is existential. Excess light from nearby buildings — and from throughout the region — creates skyglow, washing out the stars.

“As a child, I often saw the Milky Way,” Kessler said. “It’s depressing how we’ve lost our connection to it.”

Residents launch DarkSky Hopewell

Fortunately, Kessler and Krause aren’t the only ones grappling with this loss. Last year, a group of residents in Hopewell Valley came together to address the widespread brightening of the night sky.

DarkSky Hopewell was formed in 2024 to both raise awareness about light pollution, and to offer economical solutions for reversing it. The group is an offshoot of DarkSky International, a global advocacy group focused on education and research.

DarkSky Hopewell’s all-volunteer team comprises three designers, three high school students, three educators, and a scientist.

But the goal is not to plunge Hopewell into darkness, explained the group’s founder, David Ackerman. Rather, they are there to help property owners upgrade their lights to ones more appropriate for the task.

An appropriate light, according to dark sky advocates, meets all five of the following principles: it is useful, targeted, low level, controlled, and warm-colored. Most conventional lighting, such as those keeping Krause and Kessler awake, flout at least one of these principles.

“The great thing is that it’s a relatively simply fix,” said Ackerman. “You can just turn off the lights or shield them.”

Putting DarkSky principles into practice

This summer, the DarkSky Hopewell team approached Steve Ebersole, owner of Hopewell Village Square, about ten wall-mounted fixtures that blasted bright white light across the property—into people’s eyes, through nearby windows, and straight up into the sky. Studies by DarkSky International show that poor orientation alone can waste up to 30 percent of outdoor light, and these fixtures were a clear example.

The issue wasn’t only where the beams were aimed but the quality of the light itself. The bulbs emitted a cold, blue-rich glare that disrupts melatonin production and scatters easily into the atmosphere, worsening skyglow.

Ebersole had been looking for a way to reduce glare while still keeping the center safely lit, and he welcomed the group’s offer to help.

Made in Hopewell

After preliminary light measurements, the DarkSky Hopewell team offered Ebersole several design options. Ebersole selected wall pack lights that would be retrofitted with glare shields made in the DarkSky Hopewell workshop.

Ebersole’s bespoke shields were manufactured at the Highland Design Farm — the creative hub owned by Sean Mannix, an industrial designer, as well as one of DarkSky Hopewell’s members.

This compound on Van Dyke Road was converted in the 1970s from a sprawling chicken farm into an artists’ co-operative. Now, a range of techniques emerge from there, including painting, welding, wood turning, and sheet metal fabrication.

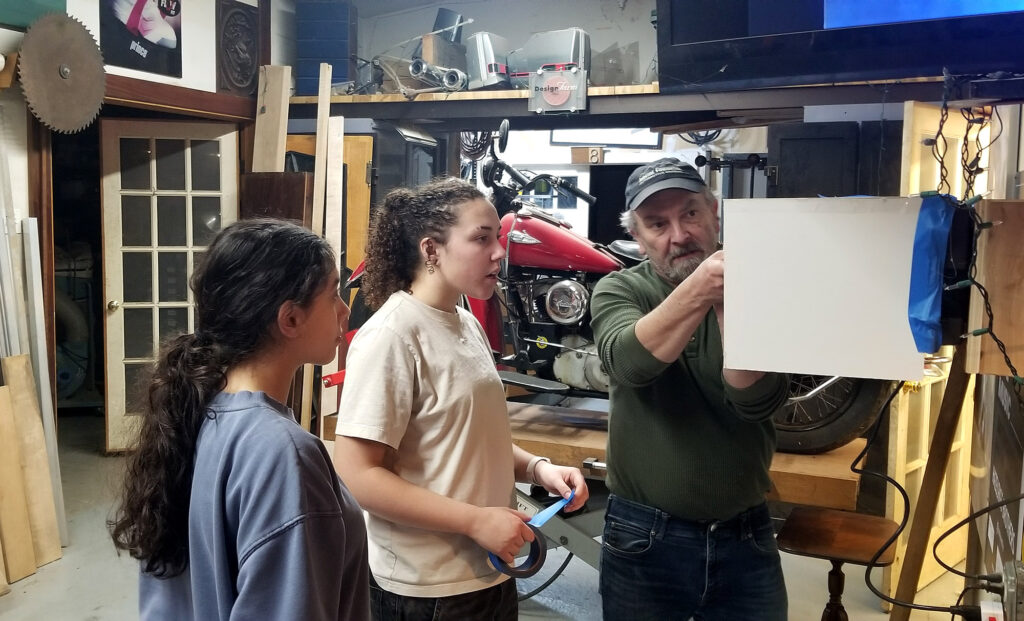

That creative energy infuses the DarkSky workshop, too. The three professional designers on the team—all of whom have expertise in bringing products to the market— work alongside three high school students in a mentoring relationship. It’s the students who draft the concept drawings and make the hand-built models. The professionals are there to guide them through the design process itself.

For Mannix, this hands-on approach is key to creating the right product for DarkSky clients. Every situation is unique, he explained, and having the ability to ask the right questions is central to designing a product the client actually wants. He worries that many of those skills are lost when students use technology to accelerate the design process.

“My traditional education taught me how to see,” said Mannix. “In this digital age, students are losing that.”

Dark sky conservation is central to the designers’ mission, but so is the ability to inspire the next generation of artists, designers, and engineers.

“Design is like breathing for me,” Mannix said, adding, “What we’re doing with DarkSky Hopewell is custom work.”

Indeed, when these custom shields were installed at the Village Square in mid-August this year, their client — Steve Ebersole — was pleased.

The energy consumption of each light had dropped by more than 50 percent, and thanks to the bespoke shields, the bulbs emitted a soft, warm glow.

“It ended up making the center more attractive and reducing glare,” Ebersole said. “It’s a win-win.”

Expanding the effort

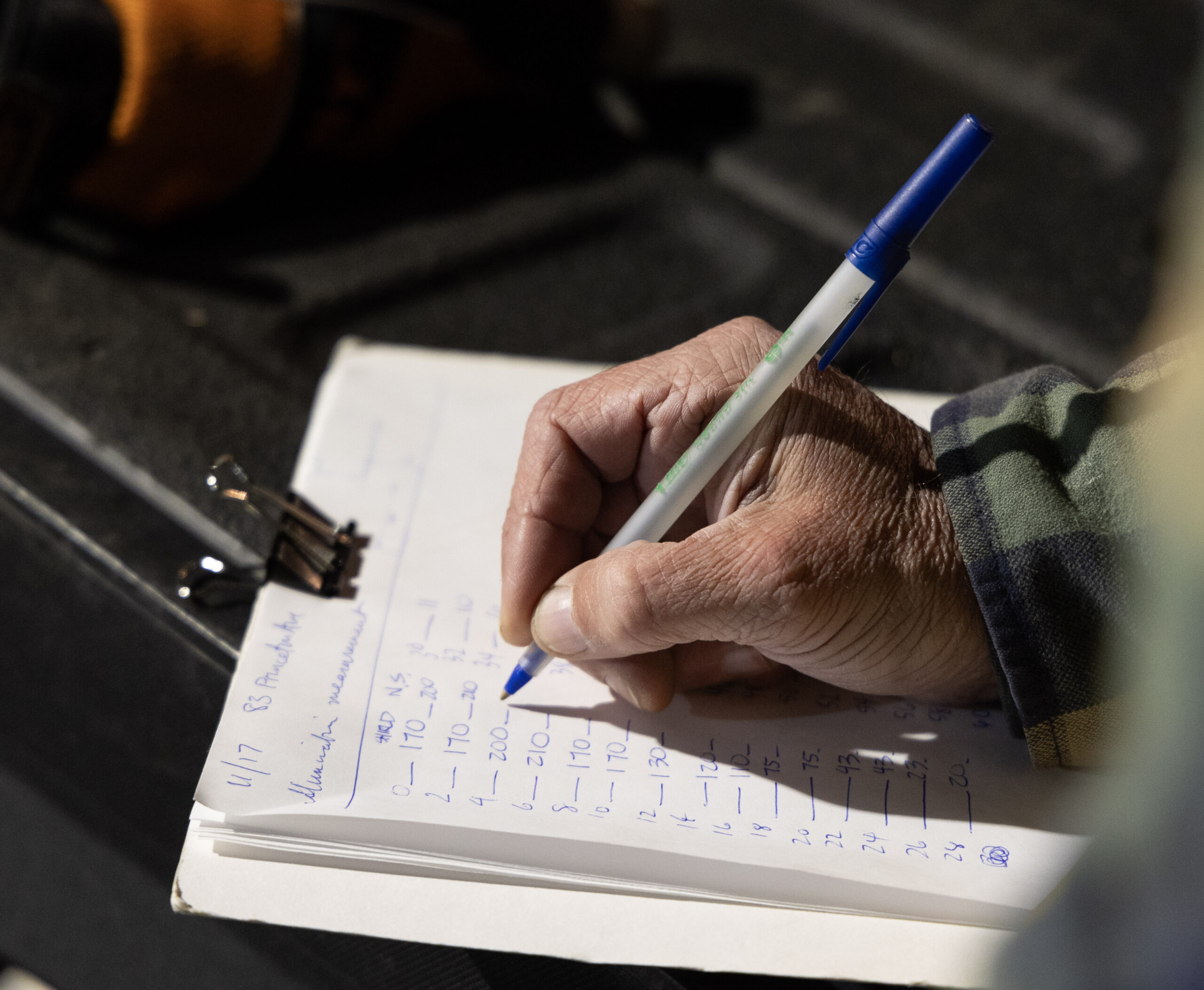

DarkSky Hopewell has since expanded its work to other properties. On Princeton Avenue, the team installed a prototype shield to curb glare from inherited lighting. Measurements taken across the parking lot showed how targeted shielding could reduce direct light trespass while preserving safety-level illumination.

Next, the group will bring the same iterative approach to the parking lot of The Watershed Institute, working with staff to design ecologically sensitive shielding tailored to the preserve’s needs.

From local fix to lasting policy

DarkSky Hopewell also works directly with residents who request help. The group is now assisting Krause and Kessler in diagnosing why nearby properties cast so much unwanted light into their bedroom.

At the same time, the volunteers are looking beyond individual fixes. They are working with Hopewell Borough officials on a proposed lighting ordinance expected to be introduced in early 2026. If adopted, it would require DarkSky-compliant lighting for new construction and major renovations — and could help position Hopewell Borough to become the first official DarkSky Community in New Jersey.

Hopewell’s effort aligns with a larger shift across the state. Several New Jersey municipalities have recently passed light-pollution ordinances, including Hopewell Township, and at least three more are developing them. These moves reflect the combined outreach of DarkSky New Jersey and the Sierra Club New Jersey’s light pollution and night skies committee, which have been educating environmental commissions and municipal green teams about dark-sky principles.

“It’s their interest that’s driving this groundswell of ordinance work,” said Steve Mariconda, DarkSky International’s New Jersey delegate. He noted that a state bill limiting light pollution from state-operated or funded outdoor fixtures is now moving through the Legislature — a measure that could make New Jersey the 21st state to enact such protections.

For Ackerman, the momentum is encouraging. He believes Hopewell Borough has a rare mix of skills and commitment to make real change.

“Occasionally lightning does strike,” Ackerman said. “I feel like lightning struck here.”