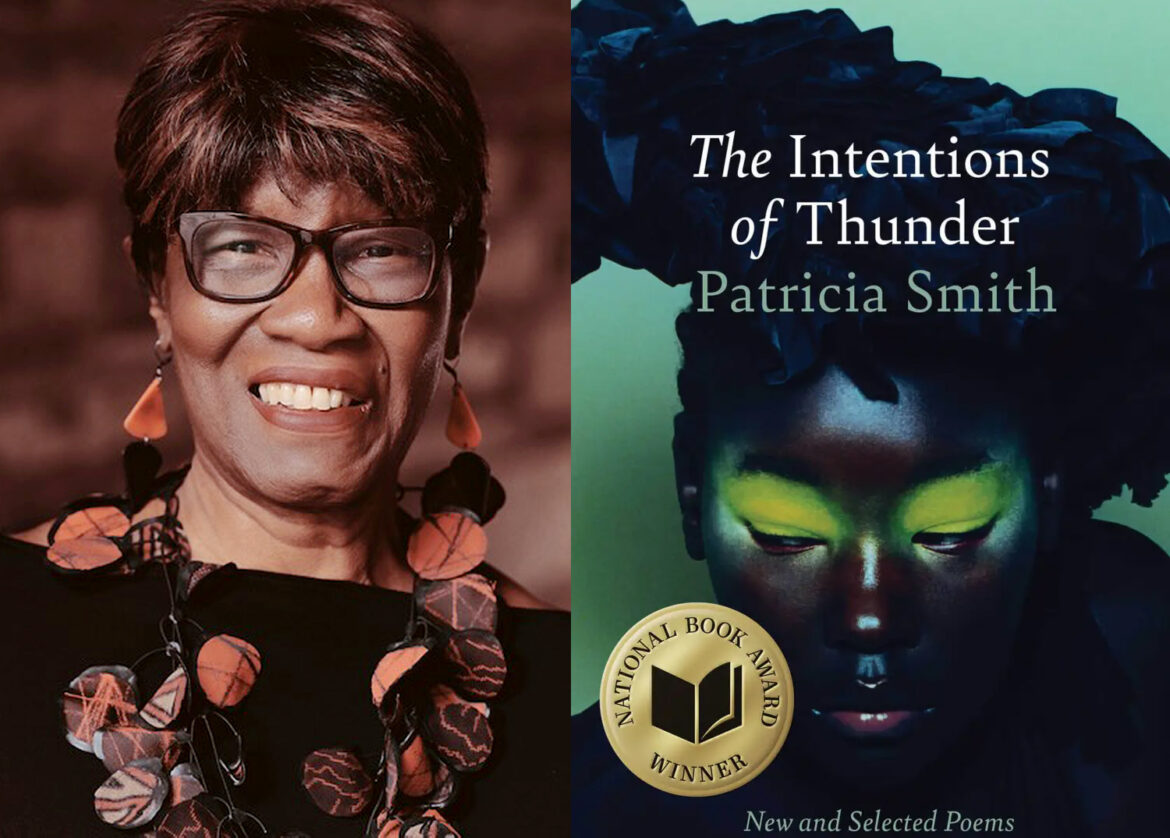

Pennington resident Patricia Smith has won the 2025 National Book Award for Poetry for Intentions of Thunder: New and Selected Poems, a sweeping, career-spanning volume that gathers new poems alongside work drawn from her many acclaimed books. The honor places one of America’s most celebrated poets — and a neighbor here in the Hopewell Valley — in the national spotlight once again.

For Smith, assembling a book that spans decades meant returning to earlier versions of herself.

“It felt a little strange,” she said. “What you wind up doing is going into all of your past books… walking back into the time and where you were in your life when you wrote those books.” Some memories were joyful, some unsettling. “You write about something you think you’re over on the other side of, and then you have to go back and relive the poem. But on the other hand, it was a culmination.”

A Poet With Local Ties and National Reach

Although Smith’s national reputation is towering — she is a Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize winner, a member of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, and a Professor of Creative Writing at Princeton University — she is also a familiar Pennington neighbor, someone often seen around town when she is not teaching, performing, or writing.

Her achievements are extensive. She is the author of more than a dozen books, including Unshuttered and Incendiary Art, the latter a finalist for the 2018 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry and winner of the Kingsley & Kate Tufts Poetry Award, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, and an NAACP Image Award. But the National Book Award marks a new capstone for her body of work — and a moment that reaches far beyond the literary world.

A Poet of the Page, the Stage, and the Community

Smith’s artistic life has always stretched beyond the page. A four-time individual champion of the National Poetry Slam, she emerged as one of the most influential performance poets of her generation. Her work has appeared in collaborations with dancers, visual artists, jazz musicians, and the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra. A dance-theater adaptation of her book Blood Dazzler sold out its Harlem Stage run, and her one-woman show Life After Motown, produced by Nobel laureate Derek Walcott, found a home at the Trinidad Theater Workshop.

For Smith, performance is not separate from poetry — it is a way into it. She believes spoken poems can create a shared space that invites newcomers who may not identify as poetry readers. “The real audience, the people you really want to reach, are not people who are already involved in poetry,” she said. “I call it the ‘community of witnesses,’ where the things that are happening to one of us are happening to all of us.”

A Childhood Steeped in Stories

Smith traces the origins of her poetic voice to her childhood home on Chicago’s west side, where her father brought with him what she calls “the tradition of the back porch.” Every evening, after dinner, he told stories — about his day at the candy factory, about neighbors passing by, about the imagined lives inside grocery bags and brown paper parcels.

“If somebody would be carrying a bag, he would go, what do you think is in that bag?” Smith said. “It would make you LOOK at the person… he would teach me that there were other ways to think about the world.”

Her earliest writings came from those conversations. “I was probably eight or nine,” she said. “I didn’t think of it as poetry… I thought all poets looked like Robert Frost.” It took years of unlearning: unlearning the assumptions about who could write poetry, what it was supposed to sound like, and who it was meant to reach.

Chicago also introduced her to her first literary hero, Gwendolyn Brooks, whose presence in the city helped Smith understand the richness she carried with her — the people, textures, and histories she once thought she needed to move beyond.

The Responsibility of Witnessing

Over time, Smith grew into an artist who moves fluidly between spoken-word traditions and the academy, insisting that poetry can — and must — belong to everyone.

“When I realized there was a responsibility in writing poetry,” she said, “I went from that recreational exercise to concentrate on what other poets were saying… and [learned] that real people read your poems, and they don’t just read them for entertainment.”

One moment, in particular, changed her sense of what poetry can do. She read a poem written in the voice of an undertaker who tended to the bodies of young people lost to gun violence. Two women quietly left the room. Both had lost sons.

“That was the first time I realized that something I wrote actually touched someone,” Smith said. “People… were searching for some kind of connection in story.”

An Award, a Legacy, and a Local Moment of Pride

Her National Book Award acceptance speech echoed that commitment to truth, vulnerability, and the act of saying aloud what might otherwise remain hidden. Speaking about her mother, Annie Pearl, Smith honored the people whose stories shaped her and the communities that continue to sustain her.

The moment, delivered on a national stage, reinforced what many here in Pennington already know: Patricia Smith’s work reaches people because it insists that human experience — in all its beauty, grief, and complexity — is meant to be shared.

As Smith puts it:

“I think we clutch secrets, and we begin to think that whatever is happening to us is just happening to us alone. And it’s not until you can say that thing aloud for other people to hear, that you realize that you are not alone.”